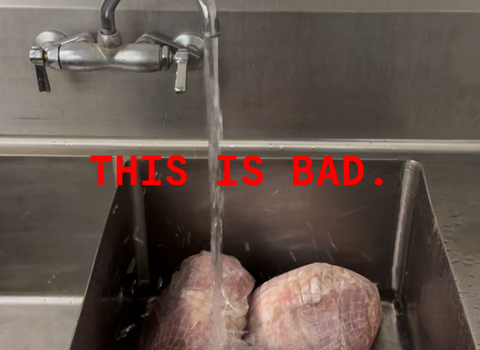

Why Running-Water Thawing Is Risky: The Hidden Safety, Cost, and Compliance Problems

Running-water thawing is still one of the most common methods in commercial kitchens — but it is also one of the least safe, least predictable, and most resource-intensive practices still in use today. What used to be seen as a convenience is now recognized by food-safety experts as a major liability.

This article breaks down why running faucets create hidden risk, what the FDA and California Food Code actually require, and why modern continuous-movement systems are rapidly replacing this outdated practice.

1. Running Water Thaws Only a Small Portion of the Food

Operators assume running water “bathes” the food, but in reality:

-

Only one point of the product is being hit by water

-

The rest sits partially exposed to warm air

-

Heat transfer is inconsistent and slow

-

Warm pockets form on surfaces above the waterline

This results in:

-

Uneven thawing

-

Temperature swings

-

Higher bacterial growth risk

Compare this to full-submersion thawing, where 100% of the surface area is in equal contact with temperature-controlled water.

See also:

Cold Water vs Walk-In vs CNSRV: Full Comparison

2. Tap Water Often Exceeds the 70°F Limit Required by Code

FDA Food Code + CA Retail Food Code require:

-

Water must be ≤70°F

-

The process must finish in ≤2 hours

But in practice:

-

Many regions supply tap water at 75–85°F, especially in summer

-

Kitchen staff rarely measure water temperature

-

Thawing times for large proteins often exceed 2 hours

-

Faucet settings drift as operators step away

This means most running-water thawing quietly violates code without anyone realizing it.

For more, see:

Understanding FDA & California Thawing Requirements

3. Running Water Allows Warm Zones to Develop

Even when the water is cool enough, running-water thawing has structural temperature problems:

-

Only the splashed side thaws

-

The top of the product warms into the danger zone

-

The underside sits in stagnant water with poor movement

This temperature stratification is why health departments treat running-water thawing as high-risk unless tightly controlled.

Contrast with continuous circulation systems, which prevent warm pockets entirely.

4. Water Waste Is Extreme — And Completely Unnecessary

Commercial faucet flow rates: 6–10 gallons per minute

Running-water thawing for typical proteins: 20–60 minutes

This means:

-

45 minutes × 8 gpm = ~360 gallons per cycle

-

Large proteins like turkeys can require >3,000 gallons

-

A single kitchen can waste hundreds of thousands of gallons per year

Hotels, groceries, and high-volume restaurants pay enormous water/sewer bills because of this.

5. Labor and Operational Problems

Operators must:

-

Monitor the water temperature

-

Adjust the faucet flow

-

Ensure the product stays submerged

-

Keep the process under the 2-hour limit

But in reality:

-

Staff step away

-

Water temperature increases

-

Items float or shift position

-

Timing isn’t tracked

This creates inconsistent results and real safety risks.

6. Why Modern Systems Are Replacing Running Water

Continuous-movement thawing systems like CNSRV DC:02:

-

Maintain water <70°F

-

Fully submerge food

-

Circulate water at ~130 GPM

-

Avoid warm zones

-

Reduce water use by 98%

-

Thaw food up to 50% faster

They eliminate the guesswork and dramatically reduce compliance liability.

Explore the technology:

👉 CNSRV DC:02 Product Page

Bottom Line

Running-water thawing is:

-

Inconsistent

-

Risky

-

Resource-intensive

-

Often out of compliance

-

Scientifically inferior to full-surface, controlled thawing

Modern operators are shifting to continuous-movement systems that improve safety, speed, uniformity, and sustainability.